The 1979 Coca-Cola 500 was scheduled for Sunday, July 29. As has been the case on multiple occasions over the decades, however, rain caused a postponement of the race until Monday, July 30.

Harry Gant won the pole for the first time in his Cup rookie career. He was driving the #47 Jack Beebe Monte Carlo and was still about 18 months from joining Hal Needham's Skoal Bandit team. Harry's car sported McCreary tires which delivered a lot of speed for qualifying but generally fell off on long race runs.

Cale Yarborough started second in Junior Johnson's Busch Beer Chevy. Rookie Dale Earnhardt lined up third in Rod Osterlund's self-funded Chevy, and Bobby Allison flanked Earnhardt in Bud Moore's Ford - a ride Earnhardt would drive in 1982 and 1983. Benny Parsons rounded out the top five starters.

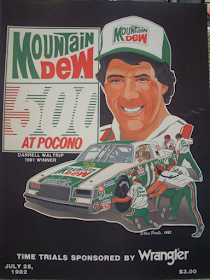

Darrell Waltrip originally qualified third fastest. In a post-qualifying practice session, however, Waltrip crashed his #88 Gatorade Chevy, and the car had to be withdrawn. Waltrip was in tight points battle with Richard Petty, and he simply could not afford to miss a race.

Waltrip's DiGard team worked a deal to rent the ride of Al "A.J." Rudd, Jr., Ricky Rudd's brother. A.J. had qualified 18th for his Cup debut in a Chevy fielded by his father. DiGard leased the car, the Buddy Parrott-led crew replaced just about every thing but the paint and number, and Waltrip lined up Monday in Rudd's 18th starting spot.

A.J. later made his first Cup start - and as it turns out his only one - about a month later at Michigan. The Michigan car likely had a boocoodle of quality DiGard parts under it from the Pocono race.

Cale grabbed the lead at the green and held it for a lap to grab a few bonus points. On the second lap, however, Gary Balough, Al Holbert, and Roger Hamby collided. Holbert's car caught fire, and safety crews had a tough time fully extinguishing it. Fortunately though, all drivers exited their cars without significant injuries.

Earnhardt passed Cale on the second lap as the yellow flag was displayed, and he held it after the race went green again through lap 14. Darrell Waltrip then took the lead for a couple of laps in the Rudd-to-DiGard converted Chevy.

And so it went for about the first half of the race. Earnhardt, Cale, DW, Bobby Allison, the King, Buddy Baker, Neil Bonnett, and Gant all got their time on the point. But any lead was short-lived and lasted only a handful of laps.

The lead changed hands a remarkable 55 times during the day. The rookie Earnhardt led 43 laps in the 200-lap race's first half.

Tom Higgins reported about the injuries in the Charlotte Observer:

He was first taken to the track infield hospital, then transported by helicopter to East Stroudsburg Hospital, where his injury was diagnosed as a bilateral fracture of the clavicle (both collarbones).

"Dale was in extreme pain...they put him on the helicopter on a board because the doctors felt there might be some back injuries, and they felt an ambulance ride would be too excruciating for him," a team member said. "The seat and steering wheel were wrenched a good bit to the left. He took quite a lick."

Earnhardt's girlfriend, Teresa Houston of Hickory, talked briefly with Earnhardt, who was sedated heavily. She said all Earnhardt could remember was the tire blowing. He did not remember hitting the wall.

With a handful of laps to go, however, Cale Yarborough had pulled out to a three seconds lead over Waltrip's #22. Waltrip seemingly caught a break when independent owner/driver Nelson Oswald, running several laps behind, blew an engine in the third turn bringing out the caution.

Second place Waltrip and third place Bonnett in the Wood Brothers Mercury both hit the pits for fresh tires. Their teams were certain the race would go back to green with one or two laps left. Yarborough's team, however, elected to leave Cale on the track. Junior Johnson knew, fresh tires or not, passing Cale on the last lap of a race would not be an easy thing to do.

But the green flag never waved again. NASCAR allowed the race to finish under yellow with Cale cruising behind the pace car and Richard Petty holding down second. The assembly of fans erupted with a chorus of "boos" as the checkered flag was displayed to Cale.

Waltrip finished seventh and blasted NASCAR saying "Isn't that some southern fried chicken feathers? I ain't no sore loser, but they should've started it back again." When told of Waltrip's comments in the winner's press conference, Yarborough smiled and said "Looks like he's a sore loser to me."

Gant found his McCreary tires were fast, but they lasted only a few laps before blistering. He finished 15th, five laps off the pace.

The race was the 28th of 31 times Petty and Cale finished in the top two spots.

|

| Source: Spartanburg Herald Journal |

After many complaints about that rule, The Overtime Line rule was adopted for 2017. Now, it seems to be in vogue for many to simply end races at the advertised distance - as it was originally. It's as if fans and media have come full circle - such as that one can make a circle out of Pocono's triangle.

Following the race, Osterlund tapped David Pearson to drive his #2 car as Earnhardt healed. Pearson had a great run in four starts with one pole, one win, no starts worse than fifth, and top 10 finishes in all four races. Osterlund, however, almost needed a B alternate. Pearson considered declining the offer to race because of a possible conflict with a commitment to work as TV color analyst.

|

| Source: Spartanburg Herald-Journal |

TMC